The Return of BEV in China: Why Pure Electric Is Staging a Comeback

How EREVs are Losing Their Edge as BEVs Surged Ahead in China’s NEV Market

Not long ago, plug-in hybrids and range-extended electric vehicles (PHEVs/EREVs) looked like the rational bridge to full electrification in China. Consumers embraced them in droves, drawn to the balance of electric smoothness and gasoline reassurance. Domestic automakers raced to meet that demand, treating BEVs as the long-term goal—but not the short-term focus.

That balance is breaking.

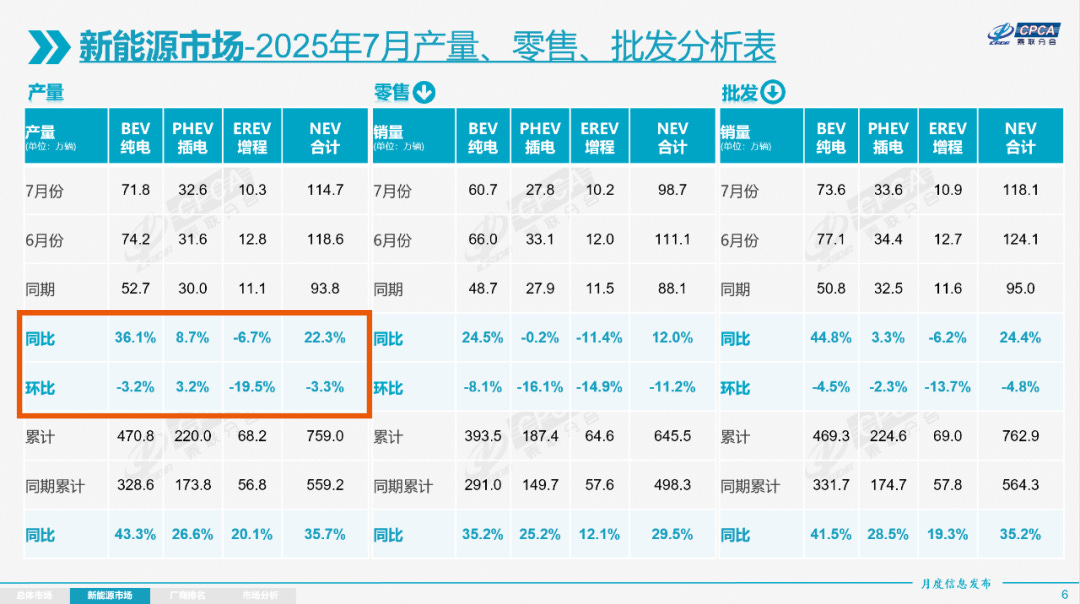

China’s NEV landscape is undergoing a reordering. In the first half of 2025, BEVs recaptured over 60% of the NEV market, growing nearly twice as fast as PHEVs. July and August sales confirmed the inflection: BEV demand is rising, PHEV growth is slowing, and EREV demand is dropping YoY. long-range BEVs are emerging as the preferred option. Even brands that built their portfolios on EREV platforms are investing heavily in charging infrastructure—an implicit admission that BEV-first strategies are the future.

What we are witnessing is not a cyclical shift. It is a structural inflection—and one that holds massive implications for China’s automakers, suppliers, and investors.

From Bridge to Barrier: The Limits of EREV

Led by Li Auto, extended-range electric vehicles (EREVs) rose to prominence as a clever workaround: smaller battery packs, no range anxiety, and faster time-to-market. At a time when battery prices were high and public charging infrastructure was underdeveloped, they offered a pragmatic solution.

But that equation no longer holds.

In China today, LFP battery pack prices have fallen below ¥450/kWh, enabling battery electric vehicles (BEVs) with 60–80 kWh packs to achieve 600–700 km of real-world range. Public charging infrastructure is now widespread, and battery swapping—pioneered by companies like NIO—offers an even faster and more convenient alternative.

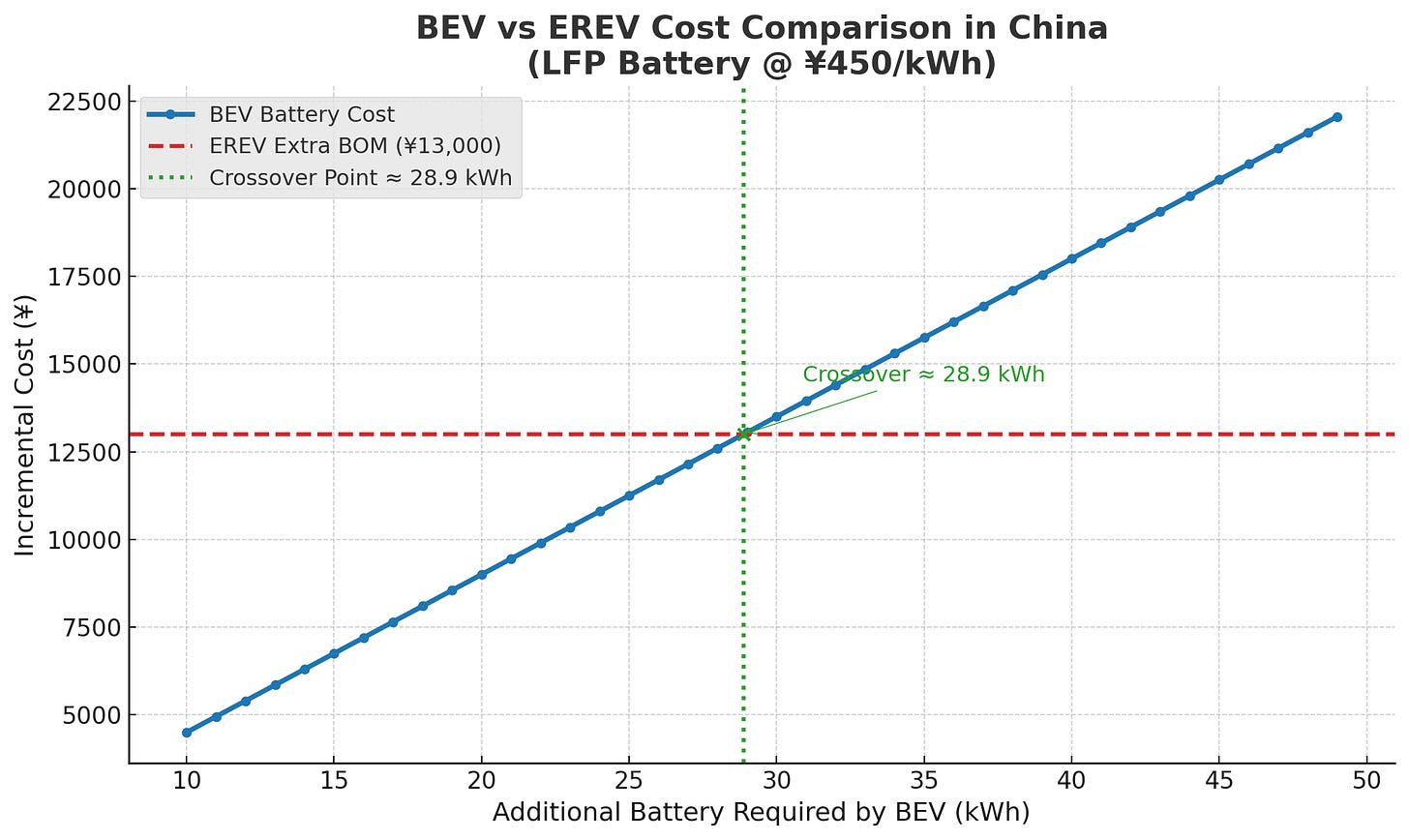

This progress has fundamentally changed the economic logic. EREVs require a dual powertrain architecture that adds roughly ¥13,000 in bill of materials (BOM) cost—covering the engine-generator unit, exhaust treatment, cooling system, and fuel components. Meanwhile, a BEV only needs an additional 20–30 kWh of battery to match an EREV’s total range. At current pack prices, the cost of that extra battery capacity is equal to—or even less than—the cost of the EREV’s internal combustion components. In many configurations, BEVs are now more margin-accretive for automakers.

The inefficiency compounds as EREVs attempt to increase their electric-only range to 400+ km. Doing so requires BEV-scale battery sizes (60+ kWh)—while still retaining the full weight, cost, and complexity of an ICE powertrain. The result is a vehicle that carries the cost burden of two systems but only fully utilizes one.

The chart below illustrates this BOM comparison between BEVs and EREVs in China, based on LFP battery pricing at ¥450/kWh:

The red dashed line shows the fixed ~¥13,000 BOM premium of an EREV’s internal combustion hardware.

The blue line charts the cost of additional battery capacity for a BEV as it increases from 10 to 50 kWh.

The green dotted line highlights the crossover point at approximately 28.9 kWh—beyond this, BEVs become cheaper to produce than EREVs on a BOM basis.

In practical terms: if the battery capacity difference between a BEV and its EREV counterpart is less than ~29 kWh, it’s actually more profitable for an OEM to build the BEV.

Viewed through this lens, the long-range EREV no longer looks like a bridge to full electrification. It looks more like a costly detour.

Why BEV Is the New Rational Choice

The return of BEV in China isn’t about idealism. It’s actually about economics and execution.

Battery costs have fallen to the point where the BOM advantage of EREV no longer holds. Regulatory pressure continues to build in favor of zero-emissions vehicles. The convenience of charging (or swapping) is improving monthly. And consumer awareness is catching up: today’s NEV buyers know the trade-offs, and more of them are choosing simplicity and scale.

BEVs are easier to build, cheaper to certify, and simpler to maintain. They reduce weight, eliminate emissions compliance burdens, and unlock new cabin configurations. And in a price-competitive environment, they preserve margin better than hybrids.

You can simply see the difference in complexity between the 2 platforms in the images below

As China’s domestic champions look to continue expanding it’s EV leadership, investments in BEV platforms are picking up steam and offer the clearest growth path forward.

An Industry Shift in Strategy

Across China’s auto sector, recalibration is underway—driven by a distinct shift in consumer behavior and confirmed by market data.

According to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), BEVs accounted for 61.2% of all NEV sales in the first half of 2025, up from 58.7% in the same period last year. Year-on-year, BEV sales grew by 38.2%, while PHEV and EREV segments slowed to 26.5% growth—their weakest since 2021. Moreover, data from CPCA (China Passenger Car Association) in July and August showed BEVs continuing to outpace EREV volume even as overall NEV growth plateaued.

The signal is getting louder: BEVs are capturing the incremental demand, especially in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities where infrastructure coverage has reached maturity.

According to data released by the National Energy Administration, as of the end of July this year, China had a total of 16.696 million EV charging connectors, representing a 53% year-on-year increase. Among them, public charging connectors totaled 4.202 million and private charging connectors reached 12.494 million (link). There are total of ~38 million NEVs on the road today, meaning that there’s a charger for every 2.2 cars on the road!

As infrastructure gets better, range anxiety improves, EREV models, once a compelling compromise, are now struggling to sustain momentum in the face of rapid BEV improvements.

In response, major OEMs are starting to shift resources accordingly:

BYD, the country’s NEV leader, has ramped up its all-electric Dynasty and Ocean series, with models like the Dolphin and Seal gaining momentum even as it continues to push PHEVs.

Xiaomi, a new entrant to the auto industry, has seen overwhelming demand for its BEV models SU7 and YU7, both of which have quickly established themselves as high-volume, high-visibility success stories.

Geely, while maintaining hybrid lines, has channeled its premium aspirations into BEV-focused brands like Zeekr.

XPeng is fully committed to BEVs, leveraging its SEPA platform and launching long-range, high-efficiency models like the G6.

And NIO, once the poster child of capital-intensive growth, is emerging as a case study in margin-focused BEV strategy. Management have stated that both the Onvo L90 and NIO ES8 have 20%+ vehicle margin, despite their aggressive pricing.

William Li, NIO’s CEO, has drawn a clear line: "The end of the range extender is pure electric." NIO has doubled down on large-format BEVs with swappable batteries, smart cabins, and user-first design. Its Q4 2025 profitability plan—centered around gross margin improvement, delivery growth, and cost discipline—relies entirely on BEV economics.

NIO’s bet is bold, but it is not alone.

Looking Ahead: Execution Over Experimentation

The bridge era of EREVs is ending in China. What we’re seeing is the normalization of BEV in the world’s largest auto market. As costs fall and infrastructure scales, BEVs now align not just with policy goals, but with consumer logic and manufacturer margins.

For China’s automakers, the implications are clear:

Product strategy must shift toward dedicated BEV platforms.

Cost structures must be engineered around larger batteries and simplified drivetrains.

Premium and mainstream segments alike must be won through differentiated software, cabin experience, and lifecycle services.

The BEV comeback is not a rebound—it’s a realignment. And in China, I believe it’ll be another watershed moment to reshape the competitive order over the next 5 years.

Interesting article but wrong in some aspects. You present Xpeng, Zeekr and Xiaomi as all in on BEVs as they have been, but they all are launching PHEV/EREVs. BYD had a hard time selling PHEVs in China this year, but see booming sales in Europe and is launching more models the next few months. China still sells 45% ICE cars, so there will still be a few more years to push the rest out. I agree that BEVs will grow as the tech get better and cheaper, but we are not there yet as of a complete replacement in most markets.